ONTOLOGY & COSMOLOGY IN I. XENAKIS’ POETICS.

FORMALIZED MUSIC : ANNOTATIONS - A CRITICAL SURVEY

Antonios Antonopoulos

Composer, PhD. candidate in Sorbonne - Paris IV & Paul Valéry - Montpellier III

aantiant@wanadoo.fr & aantiant@hol.gr

In Makis Solomos, Anastasia Georgaki, Giorgos Zervos (ed.), Definitive Proceedings of the

“International Symposium Iannis Xenakis” (Athens, May 2005),

www.iannis-xenakis.org, October 2006.

Paper first published in A. Georgaki, M. Solomos (éd.), International Symposium Iannis Xenakis. Conference Proceedings,

Athens, May 2005, p. x-y. This paper was selected for the Definitive Proceedings by the scientific committee of the symposium:

Anne-Sylvie Barthel-Calvet (France), Agostino Di Scipio (Italy), Anastasia Georgaki (Greece), Benoît Gibson (Portugal), James Harley (Canada), Peter Hoffmann (Germany), Mihu Iliescu (France), Sharon Kanach (France), Makis Solomos (France),

Ronald Squibbs (USA), Georgos Zervos (Greece)

ABSTRACT

Xenakis’ world speculation outcome seems to constitute a major adjusting factor in his first formal-ized compositions. Poetics’ initial laws, being subjected to ontological-cosmological theses combined with mathematics and modern physics, had to be invented, i.e. to become a creation anew. As Ex nihilo creation together with the Parmenidean being, keep outstanding positions in Xenakis’ reasoning, we focus on several of their philosophical aspects and epistemological reverberations. The impact of ontological and cosmological principles on poetics’ creation and compositional processes proves to be qualified with structuralizing potential, endowed therefore with functionality. Thus, ontology and cos-mology, together with the omnipresence of heuristics and intuition, lay the foundations of Xenakis’ first formalized works’ poetics.

1. INTRODUCTION. THE QUERY.

It is largely accepted that Xenakis’ thought is evenly grounded in ancient Greek philosophy, modern physics and mathematics, his work being the alloys’ proof of those, so distanced in time, entities. Except of the education Xenakis undergoes during its adolescence in the island of Spetses, his intellectual interests directed towards sciences and Antiquity, already present that time [17: 2], explain the incorporation of some mainly philosophical values in his maturity concepts. Exposing in brief his theo-retical and compositional thought in many older texts gathered in ‘Formalized Music’, he makes use of or relies on some essential philosophic principles such as being, ontology, cosmology, causality, determinism, indeterminism, continuity, chance, probability, axiomatization, formalization etc. He refers also to ancient Greek philosophers, like Pythagoras, Heraclites, Parmenides, Leucippus, Democri-tus, Plato, Aristotle and Epicurus. [22: chaps. I, (V), VIII, X]. He then provides an explanation of how he conceives these principles and interweaves them appropriately, in order to construct –with the assis-tance of mathematics and modern physics- a firm ideological and theoretical edifice leading to musical structures ex nihilo or with the least of axiomatic admissions [22: 207].

We intend to investigate, if ontology and cosmology, as generally accepted philosophical values, constitute simply an a posteriori justifying interpretation of Xenakis’ Poetics or, if these ontological-cosmological principles are of major importance, -if not anticipating scientific theories- forming the main background of his formalized work and his specific characteristic as a composer and an intellec-tual. Proceeding that way, need is to present our view of Poetics and intuition as well as those specific mechanisms, according to which philosophical values and sciences get mingled in order to produce Poetics. Adopting the resulting model, we’ll be able to have a clearer picture of the paths Xenakis’ ingenuity worked his own formalizing Poetics out.

2. HYPOTHESES – INFERENCES.

We consider as fundamental the following statements by Xenakis:

A. ‘… if it is incumbent on music to serve as a medium for the confrontation of philosophic or scientific ideas on the being, its evolution, and their appearances, it is essential that the com-poser at least give some serious thought to these types of inquiry’[22: 261]

B. ‘… these are the questions that we should ask ourselves: a) what consequence does the awareness of the Pythagorean- field have for musical composition? b) in what ways?’ [22: 207]

Answers are provided by Xenakis himself: a) ‘reflection on that which is leads us directly to the re-construction, as much as possible ex nihilo, of the ideas basic to musical composition, and above all to the rejection of every idea that does not undergo the inquiry’ and b) ‘this reconstruction will be prompted by modern axiomatic methods’ (έλεγχος, δίζησις) [22: 207].

Here is provided, virtually or theoretically, a ground position for contemporary musical composition, since we have accepted the use of music as a means, i.e. that ‘… it is incumbent on music to serve as a medium for the confrontation of philosophic or scientific ideas on the being …’ Xenakis, anyhow, has already made explicit, in a rather axiomatic manner, music’s fundamental function, which is to ‘cata-lyze the sublimation that it can bring about through all means of expression’ [22: 1]

These quotations allow inferring two hypotheses:

A. in the means of expression are included the ‘philosophic and scientific ideas on the being, its evolution, and their appearances involved in compositional process.’ These means are not ‘just consequences of mere awareness’, and therefore,

B. the means of expression might have a precise functional value, as a result of the fact that ‘for-malization and axiomatization constitute a procedural guide, better suited to modern thought’ [22: p.178] [9] and thus to contemporary composition and that ‘the Being’s constant dislocations, be they continuous or not, deterministic or chaotic (or both simultaneously) are manifestations of the vital and incessant drive towards change, towards freedom without return.’[22: xii]

The question that arises then concerns rather the way in which what is (the being) exerts its influence on the development of the compositional spirit than its own nature. However, these two fields are closely bound, because any influence, no matter how indisputable might be, couldn ever be indepen-dent of the nature of what exerts it. We are thus driven to seek the way in which Xenakis poses the problem before examining the solution he gives to it, yet without devoting ourselves to an exhaustive philosophical investigation.

3. THE BEING IN XENAKIS’ WRITINGS.

Xenakis suggests, the philosophical idea of being (Ἐόν), [22: 24,212,260] introduced by Parmenides in his poem [10] (5 th cent. B.C.E.): frg.3: τo γaρ αyτo νοεiν εστίν τε και είναι. (For it is the same thing to think and to be.) This fascinating verse has led him to the notion of not being, poetically expressed in the composer’s text, although he admits that not being takes not an absolute value (or substance): ‘…it is not a nothing, since each probability function has its own finality’ [22: 260]; in the deterministic world of mathematics, a probability function is a being and, eventually, gives creation to something, i.e. to another being. The essential problem at that time consisted in the creation of new in music, original, not generated yet: it was an almost nonnegotiable value. ‘… for these new musicians, the ma-thematical abstraction is an inspiration source as much as the abstraction of poetry. … Reference to sciences acts then at Xenakis like a source of inspiration and originality, while replacing ontological thought…. This is why the introduction of probabilities, as a principles’ founder, was very significant, since it made it possible to perceive a musical universe out of nothing’ [16: 67,82] or almost nothing. Non-causality in Xenakis’ case acts as a liberating factor. [20: 165]

The no-preexistent, however, implies inevitably and leads to the notion of existence and non-existence. Thus we slip back again to the concepts of being and non-being. Given that our query is taking place in the philosophical field first -excluding for a while and for the instance’s sake the problem of temporality- and then in the epistemological one, the question is transformed namely in: how is it possible to create something, music and musical structures in that instance, from nothing? In other words: how can we bridge the distance between non-being and being in music? But even if the explanation of the world escapes to him, by no means does he try to avoid a confrontation with ‘philosophic and scientific ideas on the being, its evolution, and their appearances’, fact with incontestable consequences in its work. ‘There is no question …to postulate that Xenakis was a philosopher with the term’s current sense; it would be disappointing the professional philosophers in advance … The autonomy of his writings -just as, in general, the writings of his contemporary composers- is of the same standard that the autonomy … of this new type of artist appearing in the 20th century that we could define with the same as Xenakis’ words: The artist-originator (Arts/Sciences. Alloys., p.13).’[16: 50]

In the executive-practical level, Xenakis solved the ‘legitimization’ problem of creating novel music, by using the least of conventions (laws or rules), as using of no principles at all, would be nor possible neither…effective. Stochastics applied in music then offered largely the possibilities of a way never explored since then. Nevertheless, it seems that he wouldn’t have been satisfied if he had turned to an arbitrary decision without a philosophical and epistemological explanatory background, even if he could have obtained the same outcome, which is musical structures ex nihilo, or approximately ex nihilo. It seems equally secure to deduce that music -and consequently musical composition- is considered by Xenakis as a being and therefore subjected to ontological and cosmological laws. In this case, both philosophical and epistemological aspects of the transition problem from not being to being remain still. Besides, temporality taken as a component of any change and consequently of all sorts of transition, the problem of time is equivalent to the transition itself. The question of the time-flow is seized according to existence [22: 259], correlated in turn with determinism and indeterminism. [22: 204-05] [12]. On this subject, Parmenides reappears: ‘And which need would have led it to be born later or earlier, if it came from nothing?’ Xenakis thus manages to exceed the obstacle of the stop of time-flow, using once again τo γaρ αyτo νοεiν εστίν τε και είναι. [22: 263].

Parmenides’ poem On Nature keeps indeed a key position in Xenakis’ reasoning: he is quoting frgs. 7:1-2 and 8:1-11 of the poem (p.203) and frg. 3 (pp.260,263); he also refers to frg. 7:5 (p.201) and 8:11once more (p.204), but without mentioning the source text this time. It seems necessary then, to focus on the Parmenidean problem of being and some of its aspects and reverberations.

4. ON THE BEING. PARMENIDES’ ON NATURE.

Parmenides, eminent figure amongst the Eleatic philosophers, was the first Greek thinker who can properly be called an ontologist or metaphysician. He is the founder of logical method. His poem On Nature has largely been discussed and commented from antiquity to our days and it is still intriguing. Plato refers to him as ‘venerable and awesome’, as ‘having magnificent depth’. Parmenides’ message, however, does not go without meeting great number of difficulties or even contradictions due to the fact that it professes a dualism opposing science to opinion and intellect to experience.

On Nature is spread in three parts, namely an introduction, then the doctrine of what is or the Way of Truth and finally the speech of appearances or the Way of Opinion (of the mortals) accounting the phenomena’s generation. In the introduction, the narration of a celestial initiatory voyage by chariot ends up with a goddess named Alètheia (Ἀλήθεια = Truth) or Mnemosynè (Μνημοσύνη = Memory) accepting the initiate and filling him with a double revelation, i.e. the doctrines of the aforementioned two ways. Truth, dealing with the universe, one , spherical, indestructible, eternal, provides the earliest specimen in Greek intellectual history of a sustained deductive argument. What is, the being , must thus be ungenerable and imperishable, indivisible and unchanging. Parmenides is concerned with the totality of what exists. Being is not for him a creative principle. Not interested in cosmogony, he is concerned with the ground of all existence: why there is something rather than nothing . What is (it) is, as a tautological sentence, becomes difficult to refute or to contradict. –In ancient Greek language it wasn’t necessary to name the positive subject (It) of the proposition; Parmenides thus passes having being the first to name significantly the being in a philosophical speech. However, we are still far from the verb’s ‘being’ duple sense by which existence and sameness of the object’s essence are both signi-fied.[15: 1165]— In Truth, the main conclusions on the nature of reality are set in frg. 8 –a part of which is quoted by Xenakis [22: 203] - and they take the form of a series of tightly knit deductive arguments. Several of these are in the reductio form to an exclusive choice between alternatives assumed to be exhaustive. However, the whole deductive chain depends on a starting point that Parmenides takes to be undeniable: the distinction between two possible ways of inquiry: ‘it is and it cannot not be’ (frg. 2:3), which may be accepted as true. But this affirmation does not possess an axiomatic form, as supported by the argument that the opposite, the other way, i.e. ‘it is not and it needs must not be’ (frg. 2:5), has to be rejected. This ought to be so, on the grounds that ‘you could not know what is not, nor could you assert it as true’ frg. 2:7,8); consequently, knowledge owes to be regulated only on being, which leads to an equation on thought (νοεῖν) and being (εἶναι) in frg.3: ‘because it is the same thing what can be thought and can be’ (τo γaρ αyτo νοεiν εστίν τε και είναι). If an investigation is to be undertaken, it must be only into what is, it is not being rejected (choice between contrary opposites). In frg.7:5 he offers what he calls ‘much-contested refutation’ , as in later Plato’s dialogs. The first conclusion shown by reductio is found in frg. 8:20 ff: ‘if it came to be, it is not’. But, as shown before, ‘it is not’ must be denied, and so we must reject coming-to-be. Movement and change have similarly to be ruled out, since they presuppose coming-to-be. To deductio and reductio ways of reasoning we can add a third one, used first by Parmenides: the principle of sufficient reason. In frg.8:6-8 ff, as an extra consideration telling for the conclusion that the being ‘is ingenerated’, he sets out the demand: ‘what need would have raised it to grow later, or earlier. Starting from nothing?’ [22: 204] If no cause is evident nor an explanation given, then we may consider the argument as being true and therefore reject the notion that it came to be at all. [5]

In

Opinions, conversely, the world of ordinary experience, based on the world as we conceive it, fails to qualify as being. Parmenides, consequently, expounds a dualistic cosmology. [2: 647]

There are surely several ways of reading Parmenides: logical, physical, metaphysical or a mid-way manner. [15: 1166] As we dispose of no evidence if Parmenides himself considered the possibility of a mid-way between being and non-being, the significance of the two ways distinction remains subject of various interpretations since Classic Antiquity. Plato is opposed to radical separation between being and non-being: there is necessarily a third way, the way of the other. Aristotle refutes the Parmenidean idea that the substance is only what is; it is what must have the potentials to be what it is not: it be-comes. It is the substantial reality itself which changes. [3: 856-7] Being thus possesses becomingness in itself.

5. THE BEING IN SCIENCES.

The text of Parmenides should perhaps be used as an occasion for modern intellect to enter another universe of thought; because how to solve the embarrassments of modern thought vis-à-vis the enig-mas of an ancient text? Essentially, this is a crucial point in Xenakis’ poetics reasoning and the main difficulty too, since creation in any field is partly synonymous of ‘coming to be’. However, this is excluded in thought, philosophically rendering any creation impossible to materialize. That is obviously wrong, since musical creation undeniably exists. We are not able to deny our senses neither our experience. In front of this impasse, Xenakis escapes literarily -and literally- by means of his famous paraphrase: ‘Because it is the same thing to be and not to be’. [22: 24,260] But, as the problem is not really solved, -except in crude practice maybe- he engages himself in demonstrating an original epistemological explanation through the Epicurean clinamen , which inevitably implies the reproduction repetitions of a phenomenon in the flow of time and the probable deviations by comparison to the regularity of its repetitions. After the clinamen, the world of probabilities set off its own course in the history of science. [22, 205] This is how Xenakis obtained the transition from inertia to ever changing compositional mobility. The description of this transition in his major theoretical writings constitutes a particular enterprise aiming to justify and make explicit his own intellectual choices in composition. The fact seems completely legitimated, provided he aims his own inventions in the field of formalization in composition and since ‘the totality of our concepts, with no exception, always constitute unfinished programs whose single validation lies in their adaptation with the task we wish them to assign.’ [24: 58]

But would an investigation in the history of sciences viewed under the Parmenidean program’s an-gle have changed the conclusions of Xenakis’ reasoning?

Parmenides was a cosmologist , even though many philosophers attribute ontology to him. [14: 6§5] The

Way of Truth reveals the real order of the world, while the

Way of Opinion describes what turns out to be a deceptive likeness of the truth and thus may be described as an illusion. The real cos-mos is a dead world, a universe without change or movement. It consists of a well-rounded spherical block, with no parts, that is completely homogenous and structureless. It has no origin and thus no cosmogony, i.e. no birth; it always was and is and always will be. Change is an illusion, motion does not exist. Parmenides, with his theory of the block-universe, became the first deductive cosmologist and the father of all theoretical physics. He discovered the theory of knowledge (epistemology nowa-days) , as he was the first to propose the method of inquiry through doubt to solve the problem of knowledge. [14: 6§6, 7§11] He also established intellectualism and rationalism and rejected of expe-rience, because it can lead only to mere opinion which is pseudo-knowledge. He was the inventor of the deductive method. His emphasis on the unchanging nature of the universe, or the invariant, may be taken as self-explanatory and a starting point in explanation and led to the search for principles of energy and momentum conservation, and also to the method of representing theories or laws of nature in the form of mathematical equations, i.e. in a process of change, something remains equal to some-thing. ‘Equations came out of tautologies, out of relations which remain true under all circumstances. Every mathematical relation is a tautology and empty in itself. … If we limit ourselves to an expression of the laws which describe only what changes compared to something which does not change, there will be place neither for something which is created nor for something which is abolished.’ [24: 97]

Parmenides theory was the beginning of the continuity theory of matter, in constant rivalry with the discontinuity theory (atomistic school) . The Eleatic School considered one reality, the continuous essence of the world, and one error, the discontinuous appearance of the world. The essence of the world, both spiritual and material, was continuous and non-evolving, because perfect continuity implied absolute homogeneity . The latter, in turn, led to total immobility, as a result of the fact that something under change, compared to something that does not change at all, creates a kind of border opposed to homogeneity. [24: 140] Total incompatibility between those theories, of continuity and discontinuity, carried out towards ground solutions of the problem of the structure of matter, down to Schrödinger and to modern quantum theory. But what Parmenides was really concerned with was the cosmological problem of change, and not a verbal argument about being. In the second part of the poem, the Way of Opinion, he describes a world order of sense illusion, of change, of genesis and destruction. He is attempting to reconcile a world of appearance -the one we experience as mortals - with the world of reality by explaining it away as a delusion, a conventional error. [14: 7§3, 4]

The problem of change may be put as follows: there must be a thing, even immaterial, that changes, and which must remain identical with its-self while it changes; but if it is so, how can it ever change? Heraclites (6th c. B.C.E.) proposed that everything is in flux and nothing at rest; there is one world process in which all individual processes merge. Parmenides replied to Heraclites by applying the original argument to the whole world: reality exists in truth, and since there is one reality it must remain identical with its-self during change. The problem then arises again: change and motion consequently, is paradoxical [14: 7§9,10]. Yet, this conclusion is refuted by experience.

In the field of physics, since we refer to a basic principle, we might hold that any physics comprises three distinct groups of postulates, no further analyzable and barely justified by our own convenience: a) Postulates representing the me (the observer) in our reasoning chains, b) Postulates forming the bonds according to which these chains will be constructed and c) Postulates forming the grounds of our real concepts, postulates which the state will be described by physics logically. If we don’t make any reasoning errors, physics so built will be an a priori construction that could be rejected only by experience. Consequently, one can neither show, nor prove that a theory is true

(verification), the experiment providing only the scale. We can only prove that a theory is false

(falsification) . Passed or present adequacy cannot in any case guarantee future adequacy, adequacy being only temporary and conditional. In practice, a theory is built so that it is adequate, but that does not change the fact that, starting from these three groups of postulates which make it up, any theory remains a plan a priori, under condition that its adequacy will be checked a posteriori. [24: 81-2] A scientific theory may be approved or sharply criticized, even rejected; nevertheless, this makes not evidence of its degree of success. A successful theory, among other characteristics, disposes of such a momentum that gives the impact for new and sometimes controversial ideas, leading either to verification (provisional, as we’ve already discussed) or, even more important, to the rise of a completely new theory by extension or by opposition to its predecessor. [9] Then the cycle begins once more and science moves forward . This is the case of the

Way of Truth and the

Way of Opinion that became the ‘way of reason’ and the ‘way of senses’, rationalism and empiricism respectively .

6. ON CHANGE AND PROCESSES.

The Parmenidean inertia was overcome by the atomists, Leucippus and Democritus (5th c. B.C.E.) According to them, motion is possible and therefore the world cannot be one full block; rather it must contain many full blocks (in the Parmenidean sense) and nothingness that is empty space. Thus, we arrive at a world consisting of atoms and the void. [22: 203] Every change, qualitative change in-cluded, is due to spatial movement, to the unchangeable full atoms in the unchangeable void [14: 7§11]. These notions have led to the discontinuity theory of matter.

Parmenides’ idea reached its highest fulfillment in the spatiotemporal continuity theory of Albert Einstein, who, by the way, accepted his classification as Parmenidean . Einstein’s deterministic cos-mology is that of a four-dimensional block-universe . The space-time continuum of general relativity implies, as often interpreted, objective, physical time assimilated to the space coordinates . Thus, the modern form of the problem of change that is of the reality of time, including time vector and its direction is attained . The main question lay in whether the fundamental temporal relations of before and after are objective or just an illusion. The possibility that Parmenides’ denial of the reality of change may indeed define the true limits of all rationality and of all science and confine us to the search for what is invariant, must be taken seriously, examined closely and criticized. [14: 7§12,16,17,19]

A point of major importance is that the block-universe interpretations commit us to metaphysical (or ontological) determinism, so that what happens in the future is fixed and subjected either to probabilistic rules or to no rules at all . There is finalism (metaphysical determinism) in the sense that we describe the evolution of the universe using general relativity physics like the need for starting from an extra-temporal state (before the Big-Bang) to carry out another (?) extra-temporal state (death of the Universe) . [7: figs.3.2, 8.1] Against what or compared to what, then, the Universe thus described might evolve? The only possible answer is: compared to an image which the observer preserves in its memory, in other words, compared to the entity of irrational, out of time and space. But this reasoning inevitably makes interfere another concept, that of the Universe of our experienced concepts. [24: 223-27] In accordance to the anthropic principle we glance at the Universe as ‘it is’ because if it was different we wouldn’t have been there to observe it [7: 224] and because we should assume that the future of any instant t of time is essentially open and only partly foreseeable and determined, both in the sense of scientific predictability and the ontological one . In addition to that, if we adopt the block-universe existence and consequently a subjective theory for time , where change and consciousness are mere illusions, then, both become an adjunct of the real world. The illusion of change is, in turn, a real illusion, because we experience change. This means that our consciousness, which is sufficiently effective in decoding the facts of our environment that are important for us, does in fact change . How can we accommodate this change in an objectively changeless world? [14: 7§20]

Concerning probabilities and the time-flow direction, concepts of major impact in the development of the 20th century physics, we ought to refer to the eminent figure of Ludwig Boltzmann , who de-scribed clearly the hypothetic-deductive method. At first, he thought that he may possibly give a strict derivation of the entropy law from mechanical premises. But when his project was threatened by the Parmenidean paradox that beset the gases’ kinetic theory, Boltzmann replaced it by another; he showed that since there are infinitely many more uniform than non-uniform distribution states, the occurrence of a system, changing from an equilibrium state to a non-equilibrium one, can be regarded as impossible for practical and statistical purposes. This gave rise to the probabilistic form of the gaze’s kinetic theory . To defend his theory, Boltzmann proceeded to the ad hoc speculation that the time-flow direction is a subjective illusion, determined by the direction of entropy increase [14: 7§23], which means a Parmenidean Way of Opinion.

For Erwin Schrödinger (quantum mechanics) objective time has no direction. Experienced time, in contrast, has a direction towards a state of increased entropy or, in other words, of increased probability. Thus, as entropy is mostly a non-reversible magnitude, time-flow is not reversible either. Today’s time theories mostly support that all three time-flow arrows, precisely the thermodynamic (entropic), the psychological (experienced) and the cosmological (Universal), point to the same direction. Generally speaking then, there is no objection in measuring time the ‘human way’ in spite of the problems to be solved in scientific practice afterwards. [7: 182-89]

The work of Andrei Markov led to probabilistic systems evolving through time, known as

stochastic systems. If the system’s future behavior depends only on its present state and not on the route by which that state was reached, the process is called a

Markov process. Such a process has no ‘memory’ [4: 663] . Probabilities resulting out of a stochastic process governed by a precise, though probabilistic, principle of evolution, are called

transition probabilities.

Max Born suggested its own interpretation of probabilities as a theory of our ignorance . Whenever we possess certain knowledge, we do not need probability theory; in the opposite case we have to apply probabilities, and this fact is in relevance to the problem we wish to solve, he said. This argument is plausible; even Einstein made use of it. The probability theory, however, was introduced in physics not because of our ignorance of a domain, but because of the nature of the problem to be solved, that is the need to predict by evaluation a system’s state under the general relativity’s continuity speculation. [14: 7§27] This is an anti-Parmenidean position, since probabilities are of non-static nature at all . Entropy measures disorder qualified by uncertainty, not by randomness (probabilistic independence). It is not an invariant in itself, and, therefore, it lies outside the Parmenidean conception, as well as the quantum physics’ indeterminism.

Heisenberg gives (uncertainty principle) a causal explanation of the breakdown of causality, by reasoning that it is due to the observers’ interference to the objects, that is to our means of observation or of measurement. On the atomic scale, it is unattainable to calculate the probability of a phenomenon’s appearance in a particular point, reality thus being reduced strictly to the whole of our observations’ results. But there is a contradiction inherent in this, namely that truth becomes just what we are able to verify, [24: 243] or to falsify (according to Popper’s theory). This implies that if there were no observers and no ‘erring opinions’ the world would be Parmenidean. [14: §28,29].

Parmenides acknowledged the task of explaining appearances and he saw the need to link the explanation of appearances with the theory of the reality behind these appearances . Specific methodological ideas are hidden under this speculation: a) the invariant needs no explanation; it can be used as an explicans, b) rational science is the search for invariants, c) out of nothing, nothing can arise (nihilo ex nihilo) , d) there must be one reality or the least of forms behind the immense variety of appearances; this leads to the conservation laws, e) the change of appearance is ruled by unchanging reality.

What Parmenides has really professed is the search for reality behind the phenomenal world, the method of competing hypotheses, criticism generalized under rationality, and the search for invariants as well. But there is need to give up identifying the real with the invariant. Whatever appears as a thing is always a process. We should thus admit the significance of change, imperfection, approximation, irreversibility, variation and transcending invariance . The distinction between things and processes may be related to the distinction between mass-points mechanics and continuous media or between particle and field theories, [14: 7§34] not to forget the late superstring theory.

To resume, the main deviations from the Parmenidean program leading to the need of its adjustment are a) the breakdown of the electromagnetic theory of matter, b) the unstable particles, that can decay into very different particles, c) the weak interaction forces, responsible for the decay of certain particles, and promising to base the direction of time upon laws, rather upon initial conditions only, d) the Big-Bang theory for the expanding universe and e) the late superstring theories.

All thoughts and facts mentioned up to this point, prompt us either to the rejection of Parmenideanism or to its radical adjustment.

7. THE BEING’S CONSEQUENCES IN FORMALIZATION.

In Parmenides’ era, the being’s material substance used to be considered as identical with the Universe’s one, which was thought as invariant that time. [8: 30,32] Today however, we know that the only invariant in the Universe remains the laws of its change. Evolution and change, then, as laws or sets of principles, are involved in the notion of being. The modern Way of Truth includes change and probability and, evidently, a certain degree of causality. No matter how apparently under-meaning it, Xenakis is quite aware of the fact. Close examination makes it obvious that he used nothing less than the Parmenidean project and its logical epistemological deductions in order to present his own vision of the world. However, he is not qualified by strict Parmenideanism, since even if he departs from the Parmenidean concept, he is using it just for the extraction of his methodological tools, causal in nature; then, he is quickly advancing towards the being’s transformations and through contemporary sciences that inspire him and excite his creative imagination , he ends up in highlighting formalization.

A question arises though: does xenakian formalizations constitute asome invariant?

Parmenides’ poem does not ‘allow’ the existence of nonbeing and therefore one should begin from being and on. As far as an idea constitutes a starting point, it is already something, a kind of object and hence a being; so ex nihilo becomes equal to the least of premises [22: 16], that is already something, followed by the search for music’s primordial elements, supposed to be invariants. As a consequence, in both Xenakis’ philosophical and compositional search, the distance between non-being and being in music has indirectly been bridged by the use of intuitive non-Parmenidean means. ‘Formalization, as a result of the quest for invariants, is an abstraction leading to universalization. The scientific way of thinking, however, is just a means serving to the materialization of the intuitive ideas’. [20: 47]

Coming back to our main query problem, which consists on how we could bridge the distance be-tween

non-being and

being in music, it seems evident that it cannot be solved through strict and static Parmenidean reasoning. After all, as already mentioned, whatever appears as a thing is always a process. The same stands for ‘…each probability function [which] has its own finality and therefore is not a nothing’ [22: 260]: this is also a process. Xenakis has given up identifying the real, e.g. a function or an equation, with the invariant. We deduce then, that, the invariant in this instance is also a process and, consequently, the same stands for formalization in Xenakis’ music: even if formalization looks like a thing it is always a process.

8. ON POETICS OF FORMALIZED COMPOSITION. MODELS AND MATRICES.

Under the general term ‘Poetics’ in art we intend a plan, a conceptual program idea, which aims or claims the production of an art work, especially in the individual level.

Behind every creative deed there exist a creator, his intuition, his intentions and his speculation about the universe. We believe that this speculation constitutes the main adjusting factor of the creation. During the Age of Enlightenment, music was thought as the art of pleasing by the succession and combination of agreeable sounds. It was a ‘decorative’ art, an ‘innocent luxury’ . Today’s music theorists and musicologists, though, consider composition having completely different perspectives. Xenakis’ music in example is thought to ‘emphasize difference than assimilation’, [6: 239-40] even when criticized .

In the present section we adopt professor’s L. Nanni Esthetic Theory theses. Nanni, carrying on his predecessors’ positions in the field, namely A. Banfi’s and L Anceschi’s New Critical Phenomenology, is equally grounded in K. Popper’s epistemology and L. Prieto’s semiotics of linguistics. With a critical spirit, Nanni borrows at Popper the concepts of both anticipatio mentis and falsification and at Prieto the notions of material object, historical object and angle-of-view. The notion of angle-of-view in particular is gradually substituted by Kuhn’s paradigm . [9] The result of the operation (metaphor?) endows the paradigm with a prevailing function all along reasoning on Poetics, either in an individual or a collective scale. [8: 61], [13]

The production procedure of an object intended to be treated as an art work leads to the suggestion of its use as such. In consequence, all kinds of work dispose of two horizons: the first of its creation and the other of its use. They are both bound together in a relation of requisite reciprocity, concerning the construction of any object, to which a certain identity is assigned, within the framework of contemporary, mainly occidental, civilization.

Restricting our search in the conceptual field of music creation, we’ll be exclusively concerned with the genesis horizon of the work, whereas genesis comprises also the process of identity attribution to a work by its creator. According to Nanni, ‘Genesis of a work-of-art’ and ‘Attribution of identity to a work-of-art’ are two synonymous concepts, as its identity converges to the practice of its use .

No matter the kind of the work to be created, one needs two a priori for the creation: first, an angle-of-view, i.e. a schedule which tends towards production, a set of laws or a paradigm. Then, as a second a priori, there is need of a material object, i.e. something to give form to; this is the world and its content in general. The identity of a material object, under which the individual acquires knowledge of a thing, is apparently identical to the manner with which it conceives it. It follows that the act of conception could not be a simple projection of the material nature of the object; our perceiving ways imply the paradigm (angle-of-view). The junction of the material object and the paradigm gives to the object its relevance or its identity. It is about a new reality, a new diversified object (because of the ‘thought’ it ‘contains’), while being of a class different than that of the material object’s.

The

paradigm, which is in need of the world in order to exist, gets in contact with this world, that is the

material object, and ‘reconstructs’ it. Thus the paradigm forms the notion of the object after having ‘selected’ each of the material object’s characteristics which might be meaningful for it (for the paradigm) and transforms it into a new defined object. When this notion takes its material expression the work is ready. (A simple schematization of the procedure appears in figure 1.) This result, the work, constitutes a third a priori, which possesses the qualities of a sign: the so-called ‘signified’, which’s ‘signifier’, constitutes the material dimension of the work. [13: 29] The work is a duple-sided symbol, where, signifier and signified, the concept and its material expression are connected with a relation not of arbitrariness, as it often happens in languages, but of necessity. [12: 265-73]

Fig. 1: A general outline of the production of an art work.

Taking under consideration that a work’s genesis coincides with the attribution of an identity to it and that Poetics is endowed with a conceptive, constructive and structural function, it goes for poetics as for the paradigm. This means that in art the term poetics might be equally replaced by the term paradigm. This leads to a model very close to that already described and tightly related with the work-of-art. Afterwards, poetics takes also care of the material expression of the work’s identity, of its realization into a materially existing object, namely of its construction. Hence the work-of-art is completed and ready to set about its life in the horizon of use. [13: 30]

If the art work to be produced is contemporary music, we need to affine our model’s notional details. Instead of material object, for instance, we’d better use the term music or world of music and respectively, the term work has to be replaced by the term composition. In no case shouldn’t we ignore the crucial role of heuristics , which combined with the composer’s inventive imagination, is mainly responsible for the whole artistic conception and the decisive interactive function between the particu-lar members of the model. All innovative ideas, intuitions and their derivatives, including the interven-tion of various philosophical or ideological values during the work’s materialization, emanate from heuristics. Heuristics, incorporating both intuition and derivability, carry along all Poetics’ steps tech-nicalities, in all the composition’s levels of elaboration.

Another major modification concerns the paradigm in contemporary music. As there is not enough space here to cover all parameters of a detailed dissertation on this subject, we’ll limit ourselves just on basically required admissions: The term disciplinary matrix has been introduced by Th. Kuhn to define a set of theories, systemic principles, laws, research and practice models according to which scientists proceed during a normal period of scientific activity. A disciplinary matrix is usually burdened with philosophical ideas and ideological values. [9: 248-250] In contemporary composition a work’s disciplinary matrix may represent the whole work as well as the composer’s style on the way of evolution. We should subsequently enclose the work’s disciplinary matrix in a wider one, the composer’s style disciplinary matrix. The previous graph may be enriched and more detailed now, as it appears in figure 2, offering a general overview of contemporary musical poetics. (d.m. = disciplinary matrix)

Fig. 2: General overview of contemporary musical Poetics.

In the case of Xenakis’ compositions, however, I believe that there is a stage anticipating poetics, and precisely, that the composer develops a d.m. that derives from the application of a scientific theory specified to this end. The aforementioned d.m., entirely built, forms an accomplished work in itself. It is apparently a duple-sided configuration, because as an accomplished work it is the outcome of a prerequisite poetics, scientific in nature, while, as of its music nature, it possesses all the core’s proper-ties of another poetics, that of the composition to derive. The entire mechanism could be described as follows: poetics is a paradigm and an invariant, but it has acquired certain notional characteristics of a work [22: 131-33], for the additional reason that its initial laws had to be invented, which means they have been generated by the composer: ‘Construct laws therefore from nothing, since without any cau-sality’. [22: 258] Poetics, under this viewpoint, even if it remains an a priori, it becomes also a work, a work anew. As such, it has to be subjected, to both

the first and the second a priori of work-creation. (Figure 3) Xenakis explicitly speaks of his creative principles in a way that allows such a deduction: he needs principles in order to use laws. [22: 182,207,Ch.X, etc.] He makes his own poetics enclosing just the scientific part of the composition’s d.m., which possesses all work’s norms. It is a process.

Fig. 3: Poetics’ mechanism depiction, implying scientific theories and philosophical values.

Deepening in our theoretical approach of poetics in Poetics, we propose the following detailed elaboration (figure 4) where philosophical ideas, ontology and cosmology in that instance, combined with sciences, namely mathematics and modern physics, give birth to a formalized work’s d.m. This scientific part of the work’s d.m. mingles inseparably with the musical part. Let us remind heuristics’ omnipresence, providing integrity throughout all steps of the procedure till the work’s completion as a formalized composition. Coherence of derivability laws and of norm applications is thus guaranteed by heuristics.

Fig. 4: Poetics leading to formalized composition (detailed schematization).

Cosmology offers models and invariants that can be used for creation or just serve as examples. But creation is not preexistent. Even if the model preexists, there must be someone who just begins using it for the first time in order to create. The world of rules needs inventors of the preexistent be this cosmological or ontological laws applied in music or in Art generally. Thus any discovery in the scientific field may eventually serve for musical creation, in both theoretical and practical directions. Indeed, within the framework of the systemic thought, a new formalization is in general born only from someone having to express something that the already existing means, as tools at his disposal, do not allow him to symbolize in a satisfactory way. The idea then should forcefully preexist to its means, if not nobody would ever seek it. When the searcher’s intellect, through its innate tendency towards objectivation of the invented formalization, comes to such a point of complication of the concepts already formed that makes the aforementioned symbolization insufficient, then, the researcher himself (or somebody else) works out a new formalization, which ends up by supplementing the old one or just substituting to it. [24: 88-89] As it regards Xenakis’ formalisms, it is clear that reacting one upon the other, the idea and its means of expression become tightly and mutually conditioned in an evolving constructive progression. Here is still one of the mechanisms of

poetics’ deployment.

9. ON COSMOLOGICAL INTUITION IN FORMALIZATION.

In connection with intuition, Xenakis considers art standing higher than sciences. [23: 18] Let us quote by that occasion an already well known passage, first published 1958 in Gravesaner Blätter no.11/12 , which could well have been intriguing some scientists of the time by its introducing parthe-nogenesis (ex nihilo). It is to be stressed that the six verses of that passage come after the famous Par-menidean verse (On Nature, frg.3) followed by a xenakian paraphrase of dionysian like inspiration:

(For it is the same thing to think and to be)

(For it is the same thing not to be and to be)

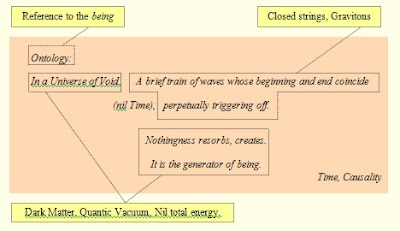

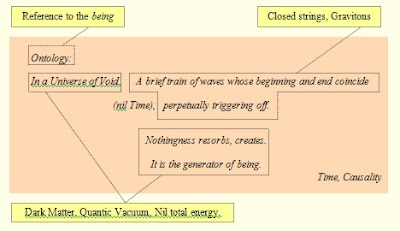

Ontology: In a Universe of Void. A brief train of waves whose beginning and end coincide (nil Time), perpetually triggering off. Nothingness resorbs, creates. It is the generator of being. Time, Causality.

What does Xenakis mean by

‘In a Universe of Void.?’ What is

‘A brief train of waves, whose begin-ning and end coincide, disengaging itself endlessly?’

If by Causality, in the sense of causal law, is meant a deterministic law, which states exceptionless connections between events [2: 123-25], then, I thing that it’s about an transcendental vision , which, today and in the scope of contemporary scientific achievements, could directly be referring to the late superstring theories, according to which matter consists of infinitesimal and periodically vibrating strings, the notion of elementary particles being thus substituted by them. Amazement is arising, if we consider that the aforementioned passage was first published in 1958, that is at a time when superstring theory had not appeared yet, not even in its early form.

A superstring model was given for the first time in 1970 by Nambu, Nielsen and Susskind, under the general name of ‘Bosonic string theory’, [11] where bosons are the carriers of forces. The ‘first super-string revolution’ occurred in 1984, same year as the excerpt from Scientific American mentioned by Xenakis in Formalized Music, p.259: ‘… there is no known observation law that prevents the observed Universe from evolving out of nothing.’ The ‘second superstring revolution’ occurred eleven years later, in 1995 [11: 144].

Superstring theories are introducing a new concept for matter’s elementary composition, reconciling thus two incompatible theories, Einstein’s general relativity with Planck’s quantum theory, promising the future unification of physics. Many physicists believe that all experimental sciences might then derive from the laws of elementary-particle-physics (reductionism), theoretically at least. If we take under consideration the concepts of unification and of reductionism, separately or jointly, we can un-derstand that certain physicists who hope to unify gravitation and quantum-physics in a single theory, a unique formalism, are tempted to consider this future theory a holistic one. [7: 193-207] However, we still ignore what the fundamental theory behind the superstring theory is; it remains primarily a speculative theory, whose experimental indices are still rare and not very convincing, although, judging from all reports explored until our days, they are promising a prolific future. [1] It seems that the measures of distance, the couples of forces and even the number of spatiotemporal dimensions are not fixed concepts but ‘flowing’ entities in interaction with our angles-of-view; [19] i.e. a modern Way of Opinion.

Since 1995, physicists consider that the cords might be bidimensional membranes or even multidi-mensional n-branes. There are five superstring types and five corresponding theories: I SO(32), IIA, IIB, SO(32) heterotic et E8 x E8 heterotic. Superstring theories originate also very important transfor-mations of space: the real world would comprise 26 to 10 dimensions curved on them (their own selves). According to the new M-theory (Mother-Theory) of Witten (1995), which unifies all existing string-theories in one, nature is likely to imply 11 dimensions. [18] A superstring measures 10-33 cm, i.e. it is equal to Planck’s length-limit and 1020 smaller than the atomic nuclei. It seems that this is the smallest matter-unit and far beyond accessibility by any observation means. [11: 136,138] Super-strings can be open or close in form (figure 5).

Fig. 5: Open and closed type strings.

In spite of its infinitesimal length (1020 less than atomic nuclei), a superstring has an immense mass-energy on the atomic scale (1019 times that of a proton) and vibrates under an enormous tension (1039 of tons) at a frequency equal to the celerity of light (2,997∙108 m/sec). Superstrings vibrate in several modes. Therefore, all different kinds of particles constitute actually manifestations of the various vibration modes of a unique superstring type in two forms, open or close. In addition to their transverse vibrations of positive energy, superstrings are also subjected to unforeseeable and ceaseless quantum convulsions, of negative energy. The 20th century particle interaction appears now as the fusion of two superstrings, [11: 131-33] represented in Feynman’s like quantum-electrodynamics diagrams (figure 6,a). The interaction’s intensity is regulated by a parameter (or coupling constant) called dilaton, which depends on the string’s oscillation mode. [19: basics/basic6.html] Dilaton’s value determines also the probability of two strings, issuing the separation of a single one, to recombine and fuse in a single string again. In this case, the diagram takes the form of a loop (figure 6,b). There can even be two, three, or more loops before the two strings do separate definitely. The probability of having loops increases in direct relation to the coupling constant’s value. [1]

Fig. 6: Superstring fusion (a) and superstring single, duple, triple … etc. coupling (b).

Although research is far from being near to an end, Superstring Theory converges towards unifying physics and provides fertile ground for new cosmologies, both of scientific and philosophical aspect, as in the case of gravitons, which proves to be of special interest. Carriers of gravitational force, the gravi-tons are superstrings of closed type, unable to be bound to n-branes and moving freely between them. Their spectrum of oscillation includes a string-particle with two units of spin, zero charge and zero mass, [19] as a result of the fact that gravitons’ quantic vibrations possess of negative energy which is subtracted from their ordinary mechanical vibration energy, which is positive. [11: 132-33], [7: 198] According to the Big-bang theory, a crucial role is been reserved to gravitons in the formation of the Universe (creation in Xenakis’ poem) or in the contraction of interstellar masses to black-holes (resorbsion respectively). [19]

We could be centered to some other particles, as well, in order to depict a number of similar examples, but this short and simplifying presentation of gravitons under the angle of the late superstring theory meets sufficiently our requirements of establishing the relations between the aforementioned Xenakis’ verses and contemporary scientific reality; because when speaking a scientific language, like Xenakis did, the expression ‘A brief train of waves whose beginning and end coincide’ corresponds effortlessly to a closed superstring or, even better, to a graviton. Equally, ‘In a Universe of Void’ and ‘Nothingness resorbs, creates’ do not express the same meaning as in daily or a current poetic speech. From this point of view, the last two expressions would probably make allusion to the Dark Matter which is invisible and fills the 85% of the Universe, the Dark Energy, an even stranger component distributed diffusely in space, or the absence of matter, that is a kind of void stuffed with energy. It is still known that the Closed Universe has nil total energy, as the energy of its mass, which is positive, is equal to its potential gravitational energy, which is negative. If then the total energy of the Universe is nil, it could logically be born from zero energy or, in other terms, ‘emerge out of nothing’.

On the other hand, the vacuum of quantum physics is a substance with defined energy density and a known pressure. Matter is hence a necessary and inevitable consequence of the laws of Void’s destruction. [21] Ontology then looks like a direct reference to the ontological facet of the notion of being, or even to the humanly experienced conception of the Universe, the Parmenidean

Way of Opinion. (Figure 7)

Fig. 7:

Fig. 7: Commented schematic representation of Xenakis’ poem (1958).

Taking into account all preceding data concerning that puzzling, if not fascinating, xenakian verses, astonishment might arise, not especially out of their intuitive poetic scientificity and, within a certain degree, prophetic allure, but primarily because of their propulsive power directly affecting the com-poser’s creative mind, as proved by his oeuvre.

10. DEDUCTIONS.

The fact that ideas related to

nothing, genesis, creation and

being lie in the source of a considerable number of

disciplinary matrices that Xenakis worked out making use of these concepts should not be overlooked. The fusion of philosophical and scientific values, driven by

heuristics throughout his poetics, gave birth to an incontestably innovative formalized musical production.

Assuming that the already presented simple deductive chain of philosophical, epistemological and semeiological thoughts offers a non-arbitrary explanation of the fact that the use of ontology and cos-mology in Xenakis poetics is qualified by a structuralizing potential and, consequently, possesses functionality, it is equally licit to support that (see: §2):

A. Indeed, in the ‘means of expression’ are included the ‘philosophic and scientific ideas on the being, its evolution, and their appearances involved in compositional processes’ [22: 207] and that they are not ‘just consequences of an awareness’. Therefore,

B. these means potentially have a precise functional value, as a result of the fact that ‘formalization and axiomatization constitute a procedural guide, better suited to modern thought’ [22: 178] and thus to contemporary composition.

I have said.

REFERENCES

1. astro.campus.ecp.fr/exposes/supercordes/supercordes.html2. Audi. R.: The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, Cam-bridge, U.K., 19993. Dumont, J.-P.: Les écoles présocratiques, Paris, Gallimard, 19914. Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought, Fontana/Collins, Bungay, Suffolk, U.K., 19775. Greek Thought, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England, 20006. Griffiths, P.: Modern Music and After, Directions since 1945, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 19957. Hawking, St.: Une brève histoire du temps, Flammarion, 1989. (1st publ. 1988)8. Karayannis, St. – Papadis, D.: Παρμενίδης ο Ελεάτης, Περί Φύσιος, (Parmenides the Eleat. On Nature.), Εκδ. Ζήτρος, Thessaloniki, Greece, 20039. Kuhn, T. S.: La structure des révolutions scientifiques, France, Flammarion, 1983. (1st publ. 1962, Postface 1970)10. Lalande, A.: Vocabulaire technique et critique de la philosophie, Presses Universitaires de France, Paris, 197611. Laliberté, M.: Les ‘supercordes’, une nouvelle métaphore musicale? in Iannis Xenakis, Gérard Grisey. La métaphore lumineuse, sous la direction de Makis Solomos, L’Harmattan, Paris, 200312. Lazaratos, I.: Τέχνη και Πολυσημία, ‘Συζητώντας’ με τον Luciano Nanni (Art et Po-lysémie,’Discussing’ with Luciano Nanni) GEOLΑB, Eκδ. Παπαζήση, Αθήνα, 200413. Nanni, L.: Della poetica, redazione provvisoria, Bologna, 199914. Popper, K.: The World of Parmenides, Routledge, London and New York, 199815. Ramnoux, Cl.: Parménide, in Dictionaire des philosophes, Encyclopaedia Universalis et Albin Michel, Paris, 199816. Solomos, M.: De l’Apollinien et du Dionysiaque dans les écrits de Xenakis, in Formel/Informel, Musique Philosophie, L’Harmattan, Paris, France, 200317. Solomos, M.: Iannis Xenakis, P.O. Editions, Mercuès, 199618. sukidog.com/jpierre/strings/mtheory.htm19. superstring theory.com20. Varga, A.- B.: Conversations with Iannis Xenakis, Faber and Faber, London, 199621. villemin.gerard.free.fr/ Wwwgvmm/Nombre/ZerPhysq.htm22. Xenakis, I.: Formalized Music, Pendragon Press, Hillsdale, N.Y., 199223. Xenakis, I.: Kéleütha, Paris, L’Arche, 199424. Zafiropoulo, J.: Apollon et Dionysos, Paris, Les belles lettres, 1961